|||> Franz Kline: a bridge between Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism |||> transmission eleven

“The thing to do is to keep your mind when you paint, to keep it free and not to let it become restricted by anything. That's the real job.”

Franz Kline

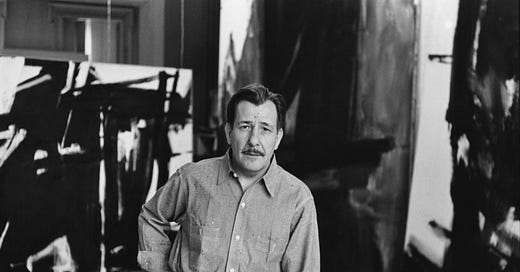

Franz Kline was an American painter associated with the Abstract Expressionist movement of the 1940s and 1950s. He was part of the informal group known as the New York School, alongside other action painters such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, John Ferren, and Lee Krasner, as well as poets, dancers, and musicians active in New York during those years.

Kline was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in a coal mining community. His childhood was marked by hardship: he lost his father at the age of seven and was later abandoned by his mother—two traumatic events that deeply affected him. He attended Girard College in Philadelphia, a boarding school for boys who had lost their fathers. In the following years, he studied art at Boston University (1931–1935) and at the Heatherley School of Fine Art in London for one year. While in London, he met Elizabeth V. Parsons, a British ballet dancer who would become his wife. The two returned to the United States in 1938. Initially, Kline worked as a designer for a department store and later as a set designer in New York, where he moved in 1939. It was in New York that he developed the artistic language that would establish his reputation. He died suddenly in 1962, just before his 52nd birthday, due to heart failure.

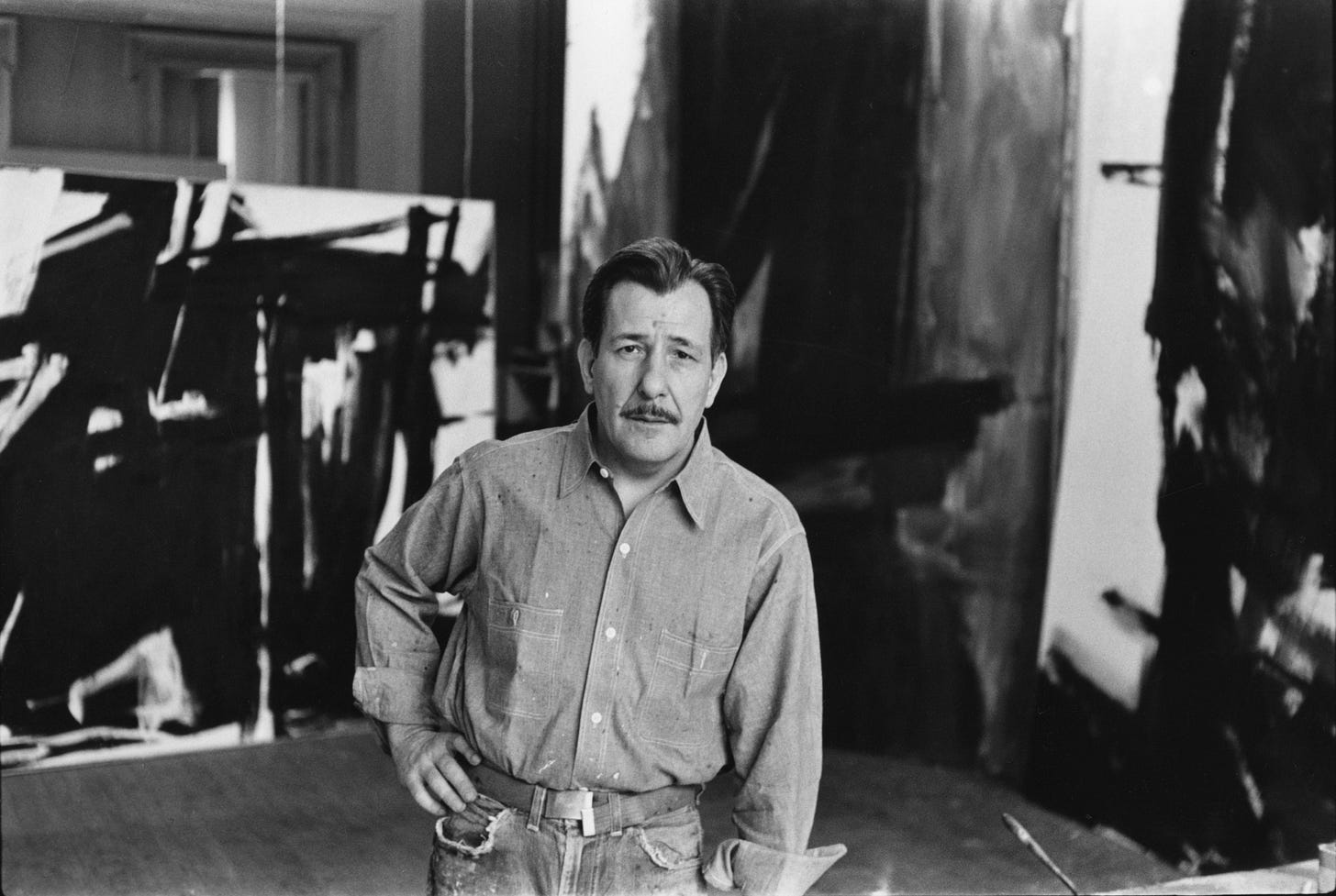

Franz Kline, Mahoning, 1956, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

His early training was focused on illustration and traditional drawing. In his first figurative works (late 1930s–early 1940s), he demonstrated solid technical skills and remarkable talent for draftsmanship. He produced landscapes, city views, portraits, and murals on commission. His emerging style can be seen in the Hot Jazz mural series from 1940, where he began to break down forms into rapid, rudimentary brushstrokes. The figures in his early works often referenced locomotives and the landscapes of his hometown, though these references were sometimes only recognizable through the title—suggesting an act of memory excavation by the artist.

Kline moved toward abstraction under the influence of the New York School artists, abandoning figurative representation and transforming it into lines and planes in a style reminiscent of Cubism. His artistic language progressively became more abstract through the use of radically simplified forms.

The most well-known narrative regarding his shift to abstraction involves Willem de Kooning who, according to Elaine de Kooning (1), in 1948 encouraged Kline to project a small sketch onto a wall, enlarging it. Kline recounted seeing, in that projection of a rocking chair, gigantic black strokes that “eradicated any image, expanding as autonomous entities.” Regardless of the anecdote’s authenticity, his late-1940s works clearly reflect an interest in isolating the formal nature of the sign. By 1950, he began working regularly on a large scale.

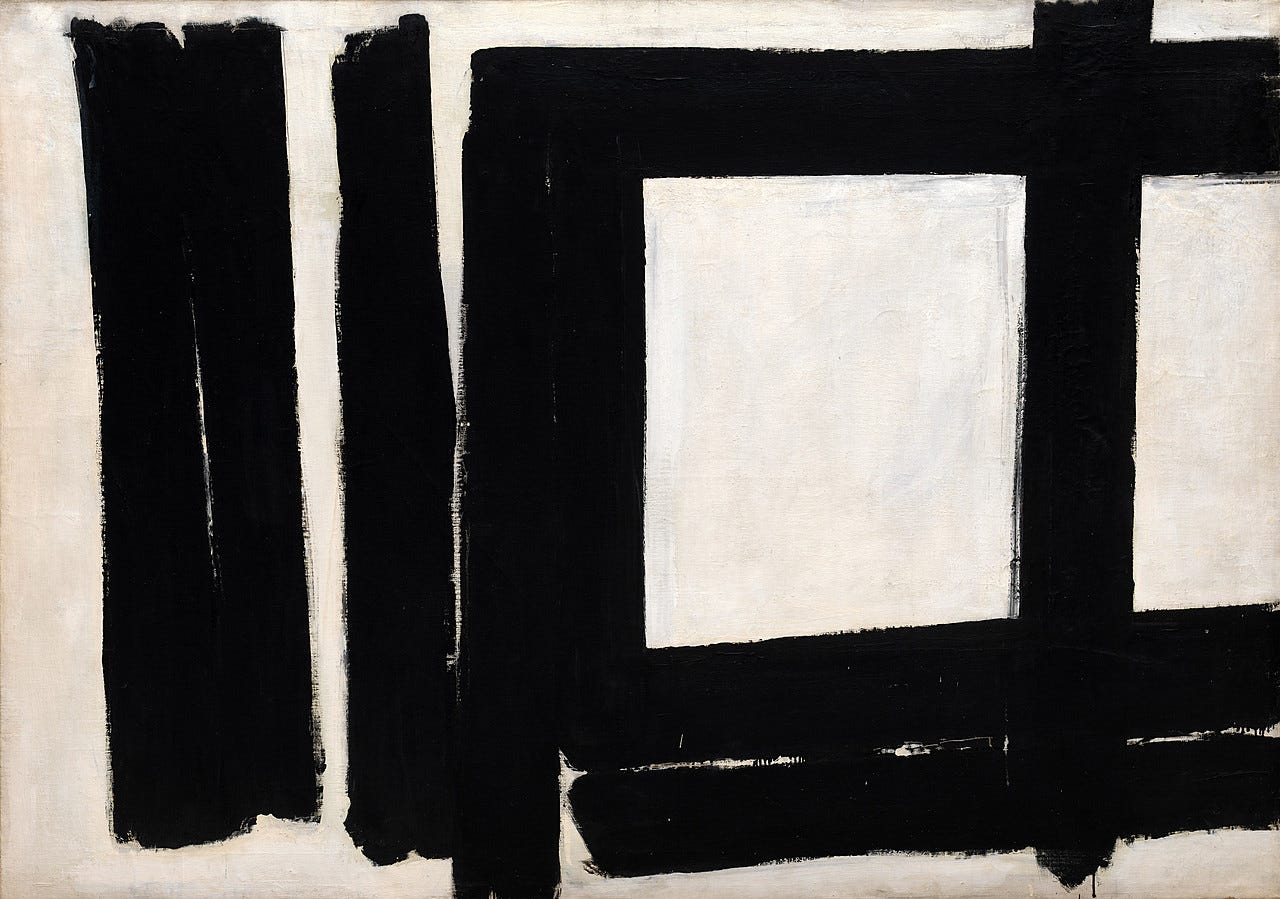

Franz Kline, Painting n°7, 1952, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

His most recognizable style is based on large black-and-white compositions. He adopted the gestural technique of the Abstract Expressionists, developing a physical and dynamic approach. However, unlike Pollock’s spontaneous compositions, Kline’s works were carefully planned, often starting with sketches made in old phone books. Robert Goldwater (2) noted that the printed text on these pages prevented illusory depth, which partly explains their appeal to Kline.

Kline considered white as important as black and actively painted both. Although some see references to Japanese calligraphy in his monochrome works, Kline denied any direct influence, even though he had contact with avant-garde Japanese calligraphers. Gestural painting, which translates creative fervor into image through the artist’s arm and brush, is immediate and impactful. For Kline, it served as a medium to express a personal poetics that lay halfway between an interiority transformed into painterly essence and an Expressionist aggressiveness: wide brushstrokes across large canvases, the dominant use of black and white, and calligraphic marks are all typical elements, clearly visible in many of his works.

Unlike many Abstract Expressionists, the American artist avoided attributing transcendental meanings to his painting. His works are not meant to represent anything beyond themselves. He invited viewers to engage directly with the marks (3) and compositions, focusing on elements such as brushstroke, negative space, structure, and color. He believed that the emotional force of a work could emerge solely from these formal qualities. This clearly reflects a search for the formal essence of what becomes sign through painting, rejecting any external meaning attached to pure artistic work.

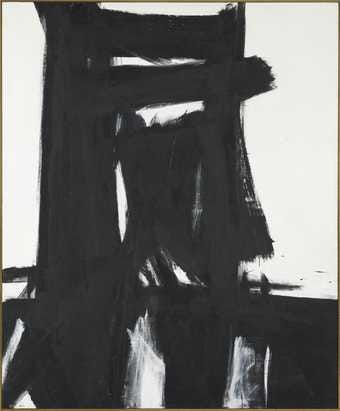

Franz Kline Meryon 1960–1, 1960-1961, Tate, London

This emphasis on formal qualities places him close to a proto-minimalist vision. Some critics see in his works an “opaque objectivity” that sets him apart from the subjectivity of the New York School, positioning him as a transitional figure between Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism.

Although his paintings may appear impulsive and dramatic, sources reveal a high level of premeditation and structural complexity. His production evolved non-linearly, experimenting with stylistic alternatives throughout the 1950s. Kline is associated with Action Painting because his works seem to express moments of strong emotion. However, the constructed nature of his paintings—where white is painted over black and vice versa, and compositions are enlarged from tiny ink and gouache sketches on phonebook pages—contradicts this notion. More than other Action Painters, Kline explored the phenomenology of emotion as something intimate and considered.

Although he is often identified as a “black and white” artist, Kline also initially worked with color. He described his shift to monochrome as a result of “painting over color.” In his early solo exhibitions, color was rare, but by the late 1950s, he had reintroduced it into his palette—sometimes as an accent, sometimes as a dominant component (Mycenae, 1958, is entirely in color). His final works display structures immersed in color, with increasing emphasis on other formal aspects.

The titles of his works often contain personal references: places in Pennsylvania, trains, people. Titles were sometimes chosen in collaboration with friends such as the de Koonings or Charles Egan.

His first solo exhibition at the Charles Egan Gallery in 1950 marked a turning point. That year, at age forty, he reached a mature and highly codified style. The downside of this early maturity was a limited potential for evolution, which prompted his return to color. His participation in the touring exhibition The New American Painting, organized by MoMA in 1958 (4), cemented his international recognition.

He taught at prestigious institutions such as Black Mountain College and Pratt Institute, influencing younger artists, including Cy Twombly (5). Sources recognize him as a central figure of Abstract Expressionism, though a complex one to interpret. His focus on formal qualities paved the way for movements like Minimalism and Post-Painterly Abstraction. His paintings are regarded as self-contained objects, not vehicles for metaphysical experiences. Artists such as Rauschenberg, Siskind, di Suvero, Twombly, and Brice Marden cite him as an inspiration.

Kline’s works were included in major group exhibitions such as The New Decade: 35 American Painters and Sculptors at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (1955); 12 Americans at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (1956); and in the traveling exhibition The New American Painting (1958), organized by MoMA’s International Program and shown in Basel, Milan, Madrid, Berlin, Amsterdam, Brussels, Paris, and London. Kline also exhibited in every edition of the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh from 1952 to 1961.

A digital catalogue raisonné of his works (1950–1962) was published in 2022.

Notes

Elaine de Kooning, cited in several articles, attributes to Willem de Kooning the role of guiding Kline’s turn toward abstraction.

Robert Goldwater analyzes the use of phone books in “Kline and the Crisis of Form.”

Kline’s statements on the autonomy of the mark appear in interviews published in Art News and Art in America during the 1950s.

The 1958 New American Painting exhibition (MoMA) is considered crucial for the European dissemination of Abstract Expressionism.

His influence on Cy Twombly is documented in the records of Black Mountain College.

Selected Bibliography

Sandler, Irving. The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism. Harper & Row, 1970.

Foster, Hal et al. Art Since 1900. Thames & Hudson, 2011.

Greenberg, Clement. “American-Type Painting.” Partisan Review, 1955.

Hobbs, Robert. Franz Kline: Art and the Structure of Identity. Whitney Museum of American Art, 1985.

Varnedoe, Kirk. Pictures of Nothing: Abstract Art since Pollock. Princeton University Press, 2006.

Sweeney, James Johnson. Franz Kline. The Museum of Modern Art, 1961.

Article compiled and edited by Enrico Marani May 15th/2025

This essay is part of a multimedia project from Spectral Unit (Adi Newton + Enrico Marani).