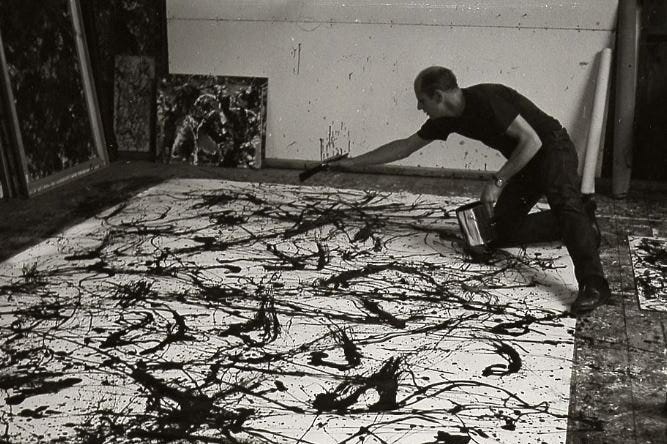

“My painting does not come from the easel. I hardly ever stretch my canvas before painting. I prefer to tack the unstretched canvas to the hard wall or the floor. I need the resistance of a hard surface. On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more a part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting. This is akin to the method of the Indian sand painters of the West.” (1)

”It came into existence because I had to paint it. Any attempt on my part to say something about it, to attempt explanation of the inexplicable, could only destroy it.” (2)

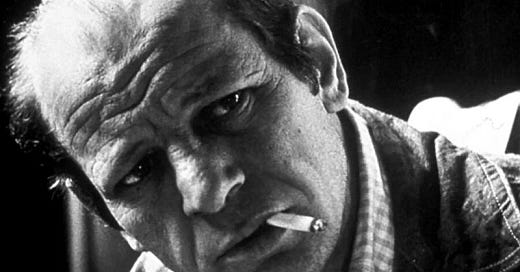

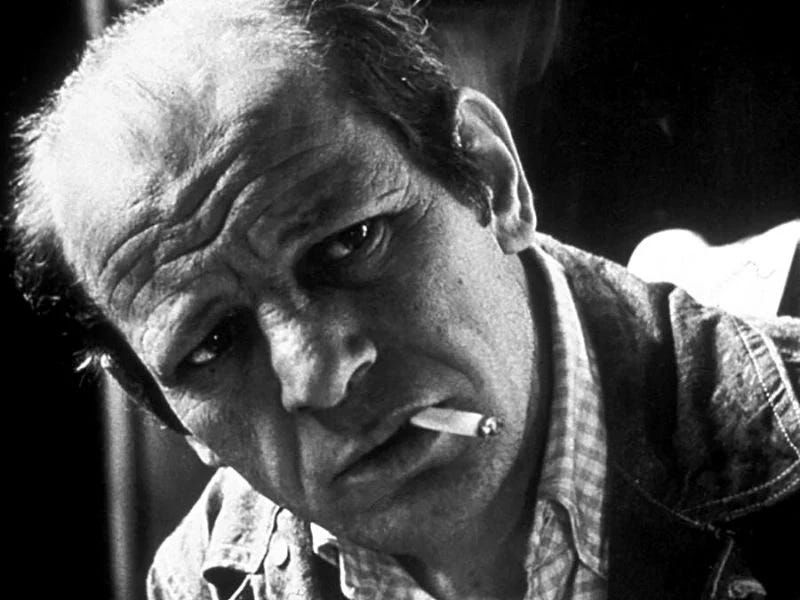

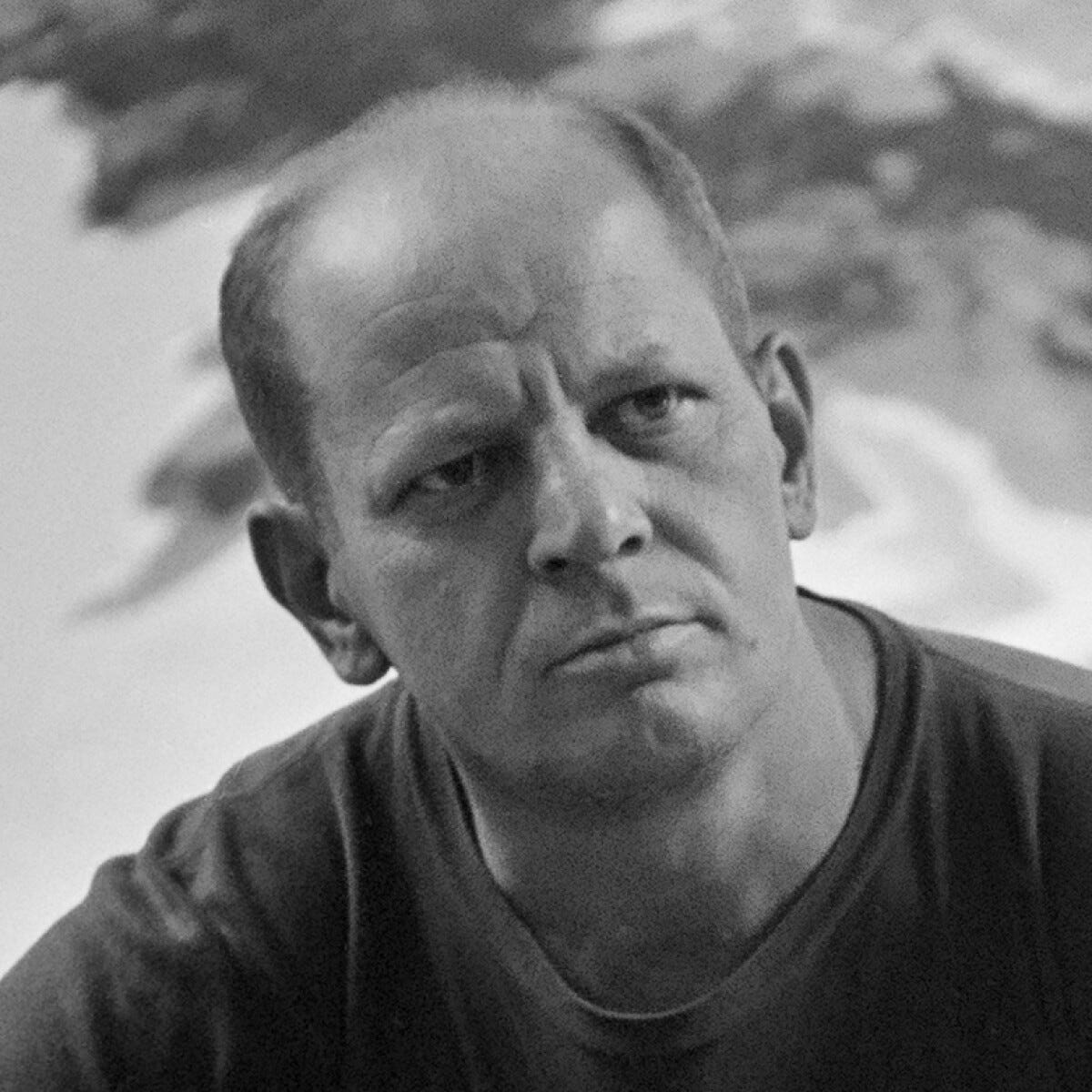

Jackson Pollock

There is a trace in Jackson Pollock's work that extends from the will to move beyond the self to connect with a ritual sphere, where the subject becomes a medium traversed by a flow of energy, with color as its precipitate. His dependence on alcohol seems to point to this erasure of the realm of reason, weakening the ego, just as Jungian analysis did, which deeply engaged the great American artist. Pollock became passionate about the study of archetypes, those unconscious models present in the human psyche. Archetypes do not develop individually but are sediments of a collective unconscious, present in people without distinction of time, as primary and inherited forms that leave their traces in myths, fairy tales, and dreams—a sort of memory of humanity which, for Jung, are the keys to accessing the unconscious. Pollock’s passion for Native American art is rooted in this discourse intersecting rituality and Jungian analysis. His painting, in particular, is conceptually influenced by the Navajo "sand paintings," where archetypal figures are created from colored pigments on a sand base in a ritual where humans are part of a timeless rituality, and truth is evident in its non-subjective nature, as the subject becomes a voice for deeper forces that transcend him.

A red thread in Pollock’s work refers to this will to become a voice for forces that surpass subjectivity, the cage in which we are trapped. His painting, starting from the early surrealist influences in the mid-1930s, brought from Europe by Duchamp and especially from the abstraction of Josef Albers and Hans Hofmann, finds its original path in making the pictorial gesture a ritual. Thanks to the patronage of Peggy Guggenheim, who commissioned him a mural for her house upon returning from a Europe now in Hitler’s hands, Pollock began to explore large surfaces—perhaps a memory of his experiences with Siqueiros and Mexican painters. However, while the works of Mexican artists allude to political epics, Pollock's goal remained, from start to finish, the search for a voice of the unconscious, touching through painting those archetypes dear to Jung and that rituality he admired in the Navajo performances.

Ritual, trance, and the obsessive consumption of alcohol are elements of his work as an artist, which in its making is effectively a performative act. The canvas on the horizontal floor and the artist dancing around and within it like a shaman is art in itself, and the painting appears as a precipitate of the gesture, a testimony. The dance is rhythm, and rhythm is an essential component of his mature work with the dripping technique. We know Pollock often listened to jazz music while working on his canvases, drawing inspiration from it and aiming to bring the sensations generated by the music onto the canvas. Music here was not just a background to inspire the artist but a direct translation of sound into painting on the canvas. These were the years of bebop, the improvisations of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, followed by giants as Miles Davis and John Coltrane.

Jazz, in its improvisational practice, seeking mood and a "dialogue" between instruments not generated by a score, but flows spontaneously, a spontaneity that transforms the musician into a vibrant instrument before any individual superstructure. The same happens with a remarkable effectiveness in Pollock's works, which appear as true jazz improvisations, wherethe artist does not paint with his hands but has in his hands and in his dripping brushes the extension of a gesture in which Pollock involves his entire body, in a sense possessed by it, but which does not yield random signs. Just as in jazz, musicians look at each other while improvising, and the discourse of one instrumentalist "responds and integrates" what has emerged from another, so in Pollock, the patterns are not a random rain of colors but a graphic score with a play of balances, a rhythmic scan where colors intersect not in a pleasant decoration but in a dramatic unfolding given also by the performative mode with which Pollock painted. This means that if improvisation in jazz is never chaos, the same occurs in Pollock's paintings, where the patterns have a rhythm, the colors define a structure, and the dialogue between different parts is evident even when concealed.

It is not pointless to emphasize how this methodology, this search for an emotional connection with creation, with art that seeks to uproot every interpretative connection to open up to an original flow, exposes the artist to a suffering in his placing himself at the edge of the human condition that constructs subjective narratives, here rejected in favor of a creative fury that traverses the body. Pollock returns to magic, to ritual, to the possessing demon, to the shaking dance, to the sprawling improvisation, and there remains his testimony among large canvases in which to drown and get lost. For what is orientation if not an interpretation of a portion of space? Jackson Pollock drags us into disorientation as a poetic practice, into the labyrinth of painting understood not as observation in a dualism but as experience in a unity.

Article compiled and edited by Enrico Marani September 1th/2024

This essay is part of a multimedia project from Spectral Unit (Adi Newton + Enrico Marani). You can watch the related Spectral Unit video and music about Jackson Pollock here.

Bibliography

Kaprow, Allan. “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” Art News vol. 57 no. 6 (October 1958): 24–26; 55–57.

Judd, Donald. “Jackson Pollock,” Arts Magazine vol. 41 (April 1967): 32–35; reprinted in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975. (Halifax: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1975): 194–195.

Pollock, Jackson. “My Painting,” Possibilities no. 1 (Winter, 1947–48); quoted in The New American Painting: As Shown in Eight European Countries, 1958–1959 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1959): 64.

Varnedoe, Kirk, and Pepe Karmel, eds. Jackson Pollock: New Approaches. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1999: 10.

Notes:

(1) from 'Possibilities' Vol. 1, no 1, winter 1947-48, p. 79; as cited in "Jackson Pollock: is he the greatest living painter in the United States?", Life (8 August 1949), pp. 42-45

(2) from David Anfam Abstract Expressionism, London: Thames and Hudson (1990), p. 87