Black and White Polyptych 1950

Fractal Expressionism in the work of Jackson Pollock

I don't use the accident - ‘because I deny the accident.

Jackson Pollock.

Pollock did not use brushes in a conventional manner, he used them as sticks to launch the paint towards the canvas without touching it. Pollock did not use common artist supplies at all; he created his personal world of materials and methods, all different from how the world had romantically come to accept how an artist should paint." What was initially read as randomness was the agency given to his tools. Even though he had an intention where to apply his next stroke, or how his next gesture would follow the previous one, Pollock had no complete control over the final mark on the canvas. While many artists experimented implementation of chance and randomness in works of art, in the paintings of Pollock randomness is not treated as a final product. In the paintings randomness becomes a generative principle that continuously inspires the ensuing performance. Accepting this model of dialectics - of continuously assessing the uncertain outcome of your own intentions - creates a new paradigm for artists to work with.

This dialectics of responding to a system that is beyond the artist's full control introduces not only a new language of painterly forms and shapes in art, but also creates a new way of thinking about making art, and what is essential to art.

Chaos. Absolute lack of harmony. Complete lack of structural organization. Total absence of technique, however rudimentary. Once again, chaos -Bruno Alfieri

While Bruno Alfieri in TIME magazine, 1950, still refers to the Jackson Pollock paintings as Chaos, Damn It, research by James Coddington at the MoMA shows that these chaotic looking, all-over paintings actually have a structured basis of straightforward and bold gestural marks.1 That initial layer enables Pollock to have visual complexity and randomness emerge from a well defined structure. Yet, even though these emergent properties are intentional, they are by no means planned, only evoked.

The embedding of nature in the work of Jackson Pollock has been demonstrated by physicist Richard Taylor, who concluded that some of the Pollock paintings were highly fractal.2 The myriad of painterly lines and spots in the drip paintings is thus of a complex geometrical character, similar to nature. This fractal aspect of the paintings is however radically different from for instance a Mandelbrot series, which is purely mathematical and a generalisation of nature's fractal character. Pollock's fractalness is the complexity found in nature.4

The well-defined initial structure in the Pollock drip paintings is continuously layered over by increasingly more gestures. As the painting evolves, Pollock immerses deeper into the painting, gets closer to the physical canvas, and narrows his frame of interaction. This results in a free scattering of tiny marks intended towards a very specific location, on top of very sharp lines less intentional in location. Thus the manifestation of randomness in the paintings moves from form (the lines) to scattering (the spots). The randomness of the marks is complicated by the merging of marks, diffusing the distinction between marks. The merging of marks depends largely on material properties and the degree the paint has dried on the canvas. Although reaction between materials can be anticipated, the ultimate outcome is uncertain. Pollock does not fully control the variables affecting the interactions of marks on the canvas; yet, their behaviour does influence the further evolution of the painting.

Jackson Pollock was one of the most influential abstract painters of the 20th century. His drip paintings were developed during the late 1940’s and early 1950’s, and they are believed to contain a mathematical, yet natural, concept called a fractal. The word fractal is derived from the Latin term “fractus” meaning broken or fractured. It is a rough, geometric object that can be subdivided into parts, each of which looks like a reduced-size copy of the whole. In a fractal pattern, each smaller configuration is a miniature, though not necessarily identical, version of the larger pattern. Fractals are referred to as nature’s fingerprint as they are heavily present in nature. Scientists claim that the juts and slopes of a specific crater in a mountain will mimic the approximate outline of a whole mountain. Therefore, what looks like Pollock randomly dripping paint onto a canvas is now speculated to be a truly complex process.Instead of using traditional painting techniques with brushes on a vertical canvas, Pollock preferred to produce a constant stream of paint splattered onto a large, horizontal canvas. A typical Jackson Pollock drip piece could take months to complete as he would constantly re-work canvases, building up dense webs of patterns. By using this “continuous dynamic” technique, Pollock was able to simulate patterns that were similar to those that evolve in nature. Fractals are essentially remnants or leftovers of the chaos theory in nature; for example, if a tropical storm was the chaos theory, the wreckage left after the storm is the fractal. The belief is that nature does not demonstrate a stable pattern, yet it does possess systems with elements of randomness that are able to organize themselves into some semblance of order. Mathematicians believe that it was through the mastery of the chaos theory that Pollock was able to create fractals in his works long before their inception into modern thought.

No 5 1948

Abstract and Avant-Garde

Mathematicians claim that fractals are the reason so many people find Pollock’s work so aesthetically pleasing. They claim that a fractal pattern, whether in a Jackson Pollock drip painting or in nature, is subconsciously pleasing to the eye. Researchers studying Jackson Pollock drip paintings are mystified and delighted at the fact that fractals are present in his work, as he was employing it decades before Benoit Mandelbrot came up with the concept in 1975 while studying fluctuations in the cotton market. It is further claimed that artists of all media, whether it is painting, literature, or music, instinctively employ fractal patterns found in nature when they create. Studies indicate that people prefer recurring patterns that are neither too random nor too regular. Of particular interest is the possibility that humanity’s preoccupation with fractals may be linked to survival more than aesthetics. On an African savannah, by tuning into fractal dimensions, people could tell if the tall grass was being ruffled simply by the wind or by a predator.

When Jackson Pollock drip paintings are meticulously deconstructed, the fractal patterns are so complex that mathematicians claim that they can determine a fake Pollock piece from an authentic one. In fact, Pollock’s fractal expressionism has been studied so closely that scientists say they can use fractal analysis to not only validate Pollock’s work, but also to date it. Apparently, changes in the fractal dimensions denote an evolution in Pollock’s style.

The drip paintings by Jackson Pollock provide an understanding of how to generate a painting by embracing the randomness of the physical system, of how to continuously interpret and respond as a mode of computing. The compositional experiments according to laws of chance by Hans/Jean Arp argue that a random point of departure has the capacity to liberate the design from unconscious customs and habits.

In the case of Pollock's drip paintings, each action however is affected by what the marks on the canvas end up looking like. This presents a computation that has indefinitely many points in the production process that may affect the course of the project as a whole. Therefore, it cannot be emphasized enough that the [ y -> y ] rule is actually the one that separates Pollock from current computational approaches. Pollock assesses the evolution of the computation by tiny step by tiny step, nevertheless allowing the generative system to have a huge impact on his intentions.

Each mark or gesture is influenced by a number of variables either controlled or affected by Pollock such as the liquidity of painting, the presence of sand in paint dried paint on stick. Yet an equally complex web of interrelated variables is present on the canvas. Each mark has a past of its own that determines its behaviour when hit by a new gesture. This past will determine whether the new mark is superimposed, whether it blends, whether it repels.

The behaviour of these individual collisions is too complex to predict. At the same time it is the eliciting of specific material behaviour that characterises Pollock. The subtle play of lines and surfaces that drape over each other are the drivers for Pollock's paintings.

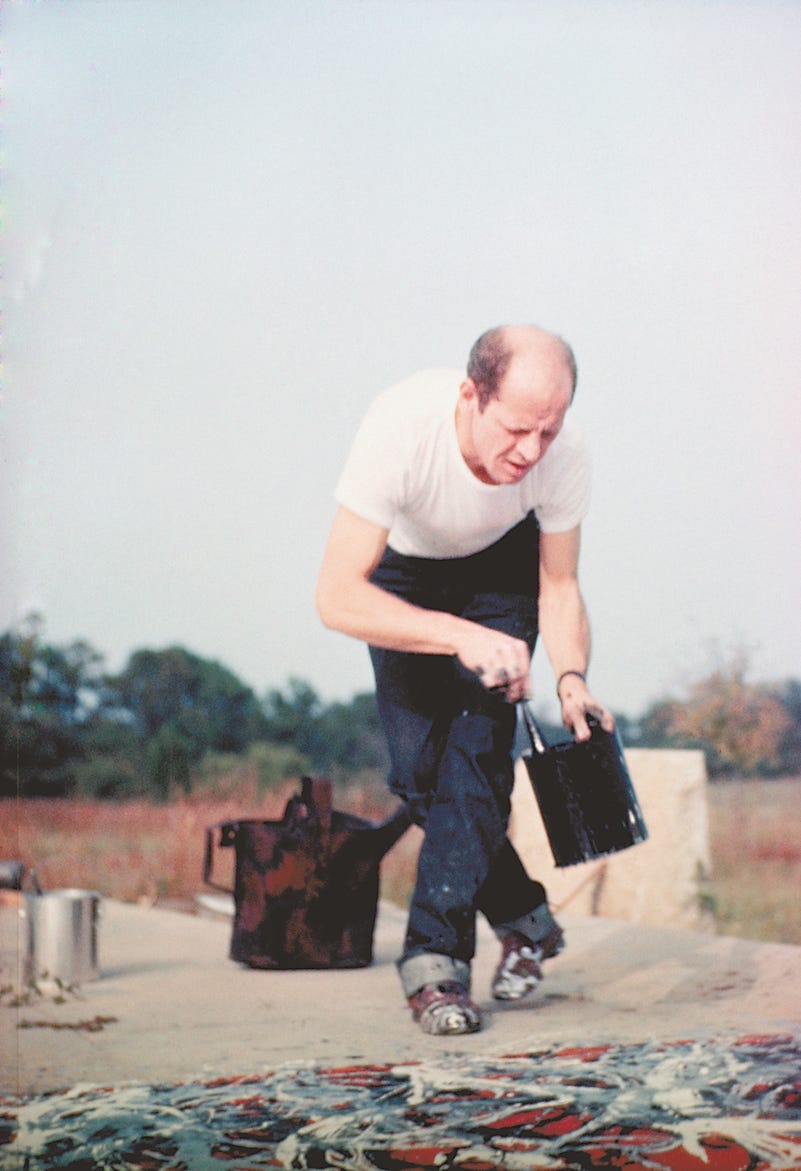

“I don't work from drawings or color sketches. My painting is direct. I usually paint on the floor. I enjoy working on a large canvas. I feel more at home, more at ease in a big area. Having a canvas on the floor, I feel nearer, more a part of a painting. This way I can walk around it, work from all four sides and be inthe painting, similar to the Indian sand painters of the West. “- Jackson Pollock

At this point it is crucial to realize that indeed Jackson Pollock looked at his paintings from all different distances, yet it was impossible to assess the full canvas from a distance. The furthest Pollock could remove himself from the canvas while painting was standing up straight, looking down on the canvas. That said, it is somewhat of an illusion to assume Pollock never saw his paintings from afar when working on them. There are several indications that Pollock would return to paintings after having the painting stored in a vertical manner in his studio for some time. Assuming that Pollock would only see the entire canvas when hung from, or placed against a wall does imply that the microstructure, rather than indeed the all-over structure drives Pollock while painting.

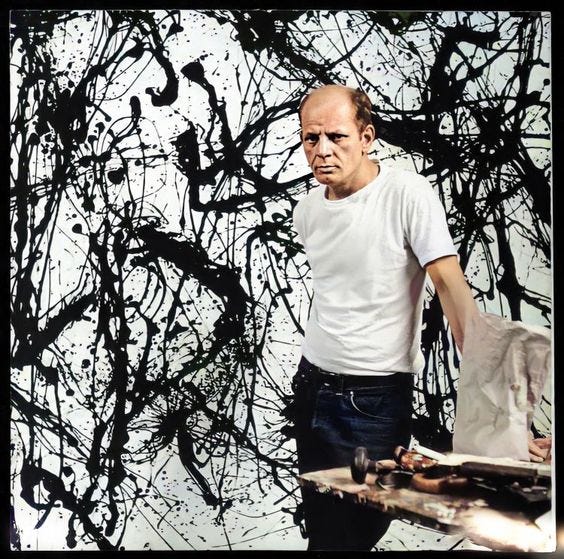

Jackson Pollock stills from Hans Namuth Film Autumn Rhythm in Summer 1951

An analysis of the 1951 film by Hans Namuth that shows Jackson Pollock working on a painting. Frame outtakes from the film have been published in a wide variety of articles on Pollock; many of these frames focus on the painter, rather than the painting. However, in 1998 Pepe Karmel published the findings of his close readings of the Namuth film. For that research he collaged film frames together to build composite images of the paintings Pollock was working on at that time. These images, and the findings of Karmel, are an invaluable resource to get a grasp of how Pollock actually treated the blank canvas.

In studying the published photographs and film fragments of Pollock in action, it has become clear how influential the Namuth photographs have been on how art history has come to view Jackson Pollock. Harold Rosenberg, for example, wrote the 1952 essay Action Painting only after seeing some of Namuth's photographs. Also, there are few published images that show Pollock looking at his work. Most of the images reprinted show Pollock in full action in his arena of paint and canvas. This seems to indicate that indeed most attention is spent on Pollock's actions.

references

1 JamesCoddington,in"No Chaos Damn It",in JacksonPollock,New Approaches, ed. Kirk Varnedoe and Pepe Karmel, MoMA, New York, 1998,

p.101-115

2 from 'Pollock, Mondrian and Nature: Recent Scientific Investigations', by Richard Taylor, invited article for 'Art and Complexity', a special edition of

'Chaos and Complexity letters

This is an edit from a much larger Article . Randomness as a Generative Principle in Art and Architecture

by Kenny Verbeeck Published by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2006

On Jackson Pollock, Fractals and Sacred Geometry

Richard Taylor, a physicist at the University of Oregon, has worked for years creating artificial retinas for patients with vision problems. His studies, unexpectedly, have led him to see the profound effects of fractal patterns on the human body, as well as their presence in nature and in art, and specifically in the work of American painter, Jackson Pollock.

For a long time, scientists in all disciplines have wondered how it is that the observation of something beautiful (however subjective the concept might seem) has effects on the human body. Why does being in contact with a beautiful sight reduce stress and improve health on so many levels?

During the 1980s, studies showed that patients recovered from surgery more quickly when hospital rooms had windows overlooking gardens or similar natural settings. These studies launched a new trend in the design of hospitals and clinics. Further research showed that even the observation of painted natural landscapes affects the autonomic response of the nervous system to stress.

But what is there in certain images, natural landscapes, or works of art, that holds this incredible power over us? Taylor’s studies found that with fractal, repetitive geometric patterns which gradually magnify themselves (they’re present in elements of nature such as plants, seashells, rivers, clouds, and mountains), lay an answer.

These powerful patterns have been replicated by man in visual art and in other disciplines; in the sacred geometry of temples and ritual expressions across all of human culture. Taylor’s studies led him to look for works of art in which they were most apparent, and so he approached the work of the painter Jackson Pollock.

Many of the paintings of the abstract expressionist, work which emerged in the 1940s, were made by emptying paint cans onto canvases placed on the floor. Pollock’s movements during the pouring of the paint were not random but responded to a kind of balance game invented by the artist. That balance is said to have had a fractal quality. Through a unique technology, Taylor’s team discovered numerous fractals in Pollock’s paintings and fractals like those found in nature. This feature, in Taylor’s opinion, is partly responsible for Pollock’s popularity.

In spite the intuitive charge they can give, the reproduction of fractals in art is neither accidental nor simple. The scientists even discovered that in several imitations of Pollock’s paintings, the appearance of the fractal patterns dramatically diminished.

Based on all of these studies, Taylor coined the term “fractal fluency.” This refers to the (profoundly simple and comforting) way in which the human eye is able to process fractals, and it’s in good part thanks to our permanent contact with nature. The process is made up of multiple stages, from the way the eye moves when perceiving silhouettes, to the parts of the human brain that are activated in these same moments.

Using electroencephalograms and measurements of electrical activity in the skin, Taylor and his team recorded and studied the behavior of the brain in reaction to these visual portents. One of their most incredible discoveries was that in observing these patterns, stress can be reduced by up to 60%. These are remarkable results for a drug-free treatment.

A reverence for beauty is perhaps one of the most essential characteristics of the human condition. And, to that point, Taylor’s studies have shown something truly inspiring: as many have long claimed, there’s an inexplicable wisdom in nature. It surrounds us and exists within us, and the intuition within the creative power of artists from all ages and cultures makes them messengers and bearers of sacred information.

Article compiled and edited by Adi Newton August 1 / 2024

Video concept, music and production Adi Newton and Enrico Marani