The tradition of modern art is a tradition of revolution: there’s one revolution after another – for better or for worse. And I think that’s what we have today: there’s been a revolution, the older Abstract Expressionists can legitimately continue working in their way, but young people have to find some other way. (1)

Adolph Gottlieb

Among the Abstract Expressionists, there are some common elements, such as being American citizens rooted in the culture of the New World, yet maintaining a strong connection with Europe, particularly through the Surrealist experience, which initially had a significant influence on their works. At the same time, however, their artistic paths reveal a distinctly American identity, belonging to a world completely different from Europe, with unique characteristics. Gottlieb's education follows this trajectory, beginning with a trip to France and Germany in 1921, where he studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris. In 1923, he returned to New York and attended the Parsons School of Design and Cooper Union. Surrealism was essential to his early work, first as an influence and then as a method. He sought to transcend any representation, figuration, or conception of the world, aiming instead to create paintings that reflect the artist's soul, the emotions that move through him, and serve as "inner writing" through painting.

Adolph Gottlieb - Icon, 1964. Oil on canvas. 144 x 100". ©Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation.

In 1937, he traveled to the Arizona desert with Rothko, where he came into contact with Native Americans and their forms of expression, characterized by the essentiality and geometry of forms. This interest in Native expressive forms, as a definitive break from the Academy and a recovery of ritual expressive modes, is another characteristic shared by many Abstract Expressionists, marking a difference from the artists of the Old World, who primarily embraced primitivism as an aesthetic fascination with formal consequences. Not coincidentally, following his stay in the desert, Gottlieb created his first series of significant works: the Pictographs. These are characterized by a fixed grid in which simplified figures, symbols, and signs of an indecipherable script find a place—hieroglyphics of the unconscious, expressions that resist interpretation, resolution, remaining as questions and mysteries rather than becoming an alphabet. These works represent the artist's first attempts to reconcile elements of abstraction with an exploration of the subconscious. To create these pieces, Gottlieb employed a process of free association and intuition influenced by the Surrealist technique of automatic drawing. Drawing inspiration from eclectic sources, including non-Western cultures and modern art, Gottlieb invented a pictorial language that aims to represent and convey universal ideas to the viewer without appealing to their rational sphere.

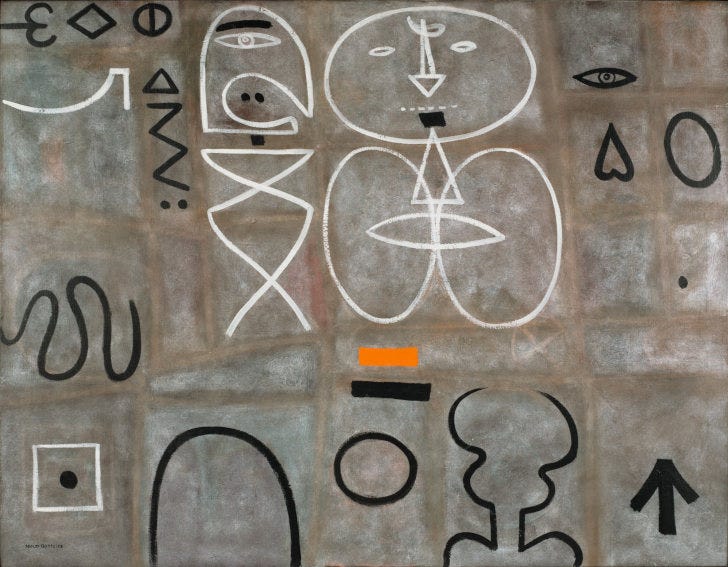

Adolph Gottlieb - Man Looking at Woman, 1949. Oil on canvas. 42 x 54" (106.6 x 137.1 cm). Gift of the artist. © Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. MoMA Collection.

The Pictographs are visual compositions, a direct consequence of Gottlieb's journey to Arizona, mediating the Surrealist influence with inspiration drawn from African art and, above all, Native American art—expressive forms that the American artist also collected. It is essential to note that Gottlieb never intended the Pictographs to be decipherable representations constructed to reveal a symbolic universe reducible to language. Instead, they were meant to be opaque paintings, without any esoteric construction behind them to be unveiled, directly inspired by his familiarity with diverse sources, such as prehistoric objects, tribal arts, European classical art, and contemporary painting and sculpture. For Gottlieb, "the artist's role, of course, has always been that of the image-maker. Different times require different images." With the Pictographs, we have a "creative machine" for processing different sources into a non-hierarchical whole. His artistic maturity came from the 1950s with the series of paintings known as the "Burst," which began in 1957 and continued to expand until his death in 1974. The visual language of these paintings is simple and direct: the canvas is divided into two zones, upper and lower. The upper zone features one or more circular shapes in a limited range of colors, while the lower zone is filled with a frenzied, gestural explosion of chaotic and swirling energy, often painted in black. For Gottlieb, the series synthesizes the ultimate expression of his core idea: in the universe, polarities exist simultaneously, such as darkness and light. Conventional wisdom tends to describe these forces in a dualistic manner—as if light were fundamentally the opposite of darkness. Gottlieb understands and represents light and darkness as elements of varying intensity but part of the same matter.

Adolph Gottlieb - Burst #3 1964-1965. Acrylic and ink on paper 24 x 19 in. (61 x 48.3 cm.)1964 "3". Private collection.

One can become the other with the slightest impulse from existing forces, and the two zones in his paintings operate similarly, not through opposition but interpenetration. The circular forms appear balanced, floating above what looks like a tumult. But both are part of the same canvas, and neither is in a state of granite-like immobility. What is above can descend, and what seems chaotic can, under the right circumstances, rise and become one. In the "Burst" series, where Gottlieb reaches total expressive autonomy, the visual structure is simple yet powerful, condensing all the themes of his artistic exploration. The contrast between order and disorder, balance and explosion, creates a dynamic tension that is both visual and conceptual. The vibrant colors of the upper disc often contrast with the darker, more dramatic tones of the lower explosive form, creating an intense visual effect. While the shapes are abstract, many critics and art historians interpret and assign rational designs to these forms, but Gottlieb is reluctant to provide definitive explanations, preferring that the works speak for themselves, presenting themselves to the viewer as an enigma. There is undoubtedly, in the "Burst" series, an extreme reduction to essence between two polarities—one evidently more stable and balanced, the other where dynamism, transformation, becoming, and entropy are evident. However, there is no chasm between these two worlds, but rather an osmosis, an exchange, in which the viewer is not merely a spectator capable of deciphering what is happening, but is part of the work itself. This impenetrable symbolism reduced to essence brings Gottlieb closer to Japanese art, where the gesture resolves the dichotomy between the immobility of order and the continuous dynamism of becoming into a unity. An essence.

Article compiled and edited by Enrico Marani April / 2025

Music and video concept and production Adi Newton and Enrico Marani

Bibliography

Ashton, Dore. The New York School: A Cultural Reckoning, New York: The Viking Press, 1972,

Russel, John. The Meanings of Modern Art: America Redefined, Volume 10, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1975

Graham, Lanier. The Spontaneous Gesture: Prints and Books of the Abstract Expressionist Era, Canberra: Australian National Gallery,1987

Anfam, David. Abstract Expressionism - World of Art Series, London: Thames and Hudson, 1990

Flam, Jack. Primitivism and Twentieth-Century Art: A Documentary History, Berkeley: University of California, 2003

Gottlieb Adolph. Vertical Moves: Pace Wildenstein, 2002

Notes

(1) from Andrew Hudson. interview, Washington Post: “Gottlieb finds Today’s Shock-Proof Audience Dangerous" July 31, 1966