The progression of a painter's work, as it travels in time from point to point, will be toward clarity: toward the elimination of all obstacles between the painter and the idea, and between the idea and the observer. As examples of such obstacles, I give (among others) memory, history or geometry, which are swamps of generalization from which one might pull out parodies of ideas (which are ghosts) but never an idea in itself. To achieve this clarity is, inevitably, to be understood. (1)

Silence is so accurate.(2)

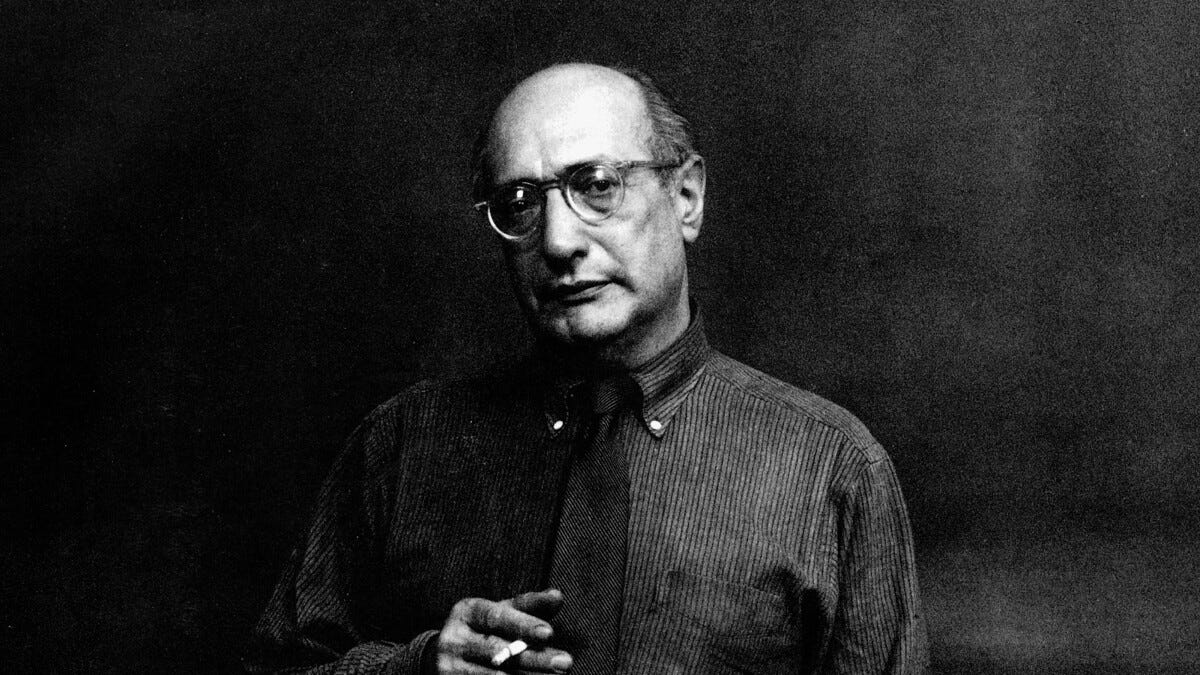

Mark Rothko

The work of Mark Rothko climbs, like Sisyphus, towards a sublime that eludes in a contemporaneity that has been experiencing a crisis of the Sacred for over a century, marked by the ignorance of all rituals, the loss of memory, and the dispersion of symbols. Rothko seeks the extreme of an infinite which he approaches through painting, while life continually throws him back, making it impossible to remain in the infinite; thus, his artistic endeavor is destined for failure, according to human logic. In his mature works, nothing happens, nothing appears, and apart from the layered experience of color in its purity, nothing else is granted to the observer. Large canvases, which the artist recommended observing up close, lead to an experience reminiscent of Heideggerian "being-there," in an emptying of descriptive experiential data, a narrative void, an experience that is alien to what we subjectively perceive as reality. If you prefer, dedicating yourself determinedly to Rothko means meditating, where meditation is not about getting lost in the turbulent streams of thoughts and emotions, in a current of facts, events, memories, desires, impulses, but rather observing them without identification, an operation that leads to an evaporation of the contingent, into a direct experience of contact with consciousness that is not confined within a perceptual realm and is not measurable.

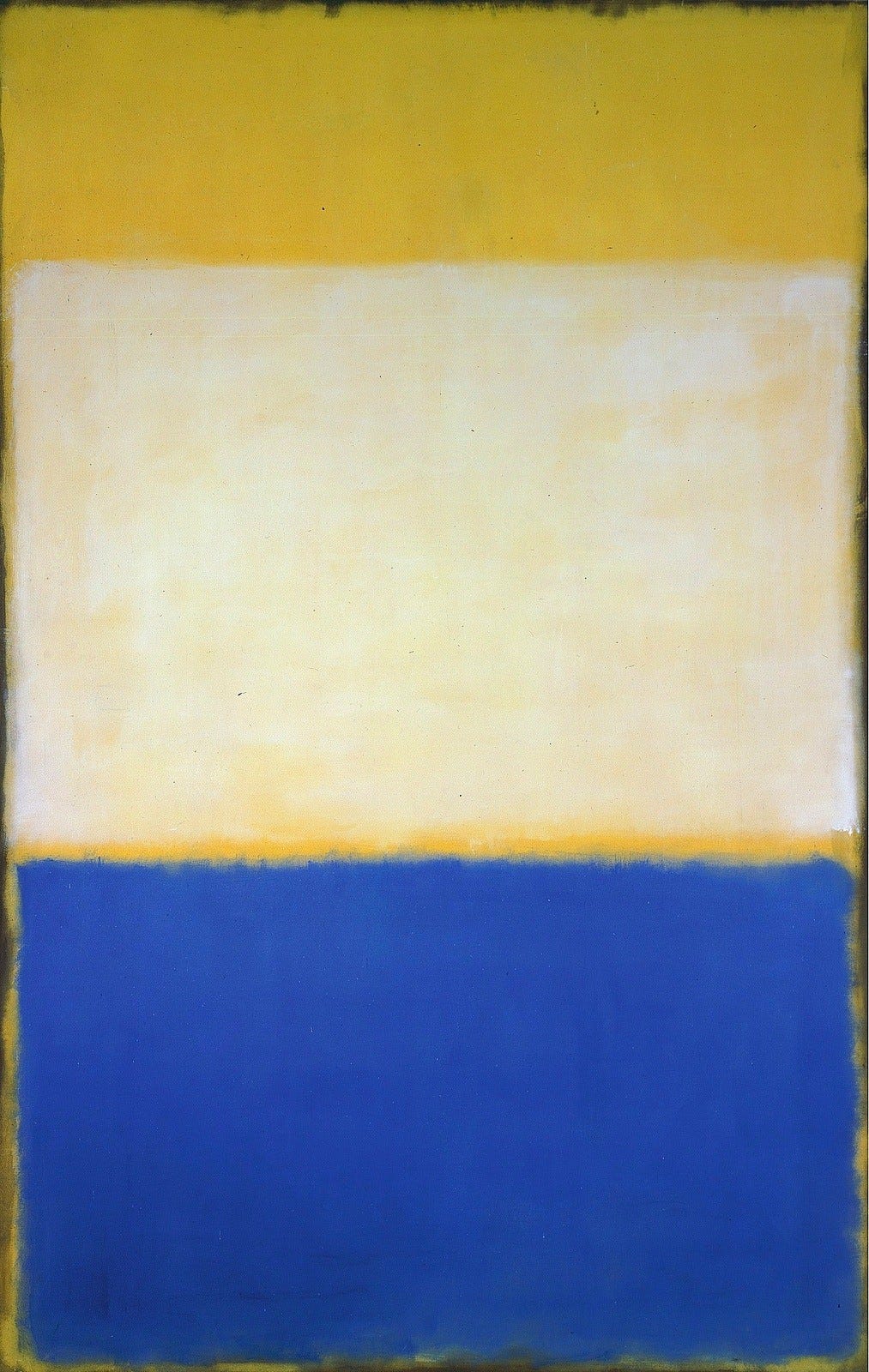

Mark Rothko, No.6 (Yellow, White, Blue over Yellow on Gray), 1954, oil on canvas, 2,4 x 1,5 m. Collezione Gisela e Dennis Alter.

There are colors of a spectral appearance so-called because they are located at indefinable distances. In the paintings of Mark Rothko, these colors manifest themselves, progressively occupying the entire visual field, following a stylistic shift that occurred after a period of inactivity. For a whole year, the American artist stopped painting and devoted himself solely to writing. This period of inactivity seems to have influenced the turn that would lead him to develop the style for which he is known today.

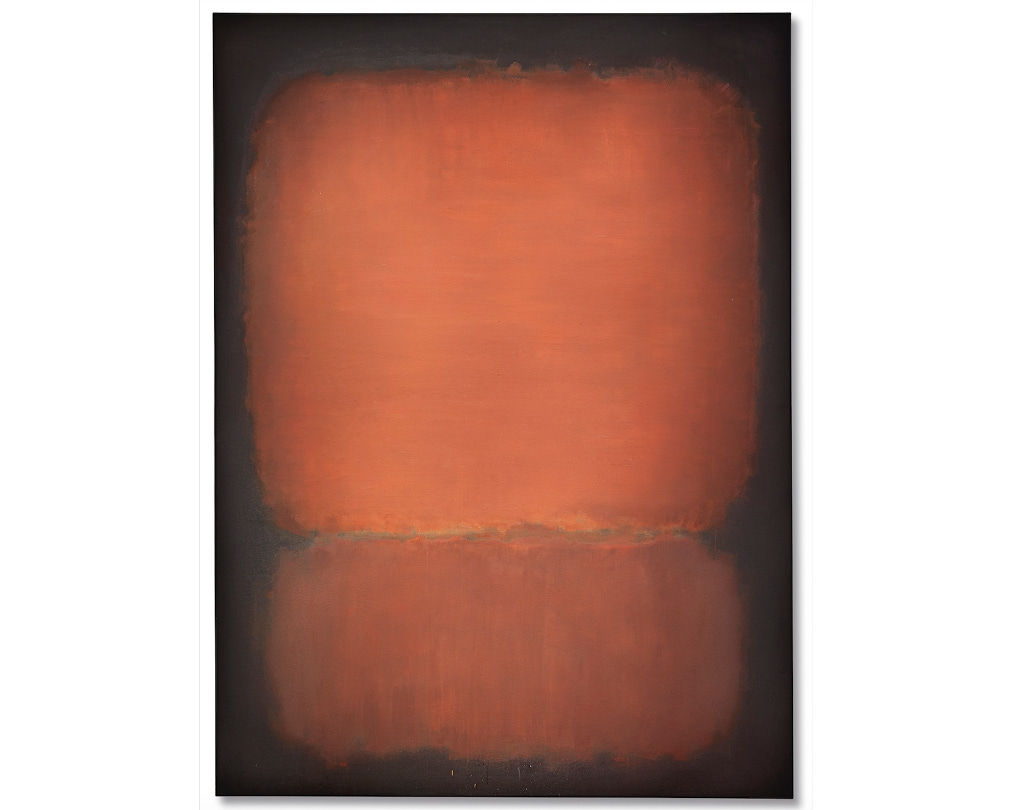

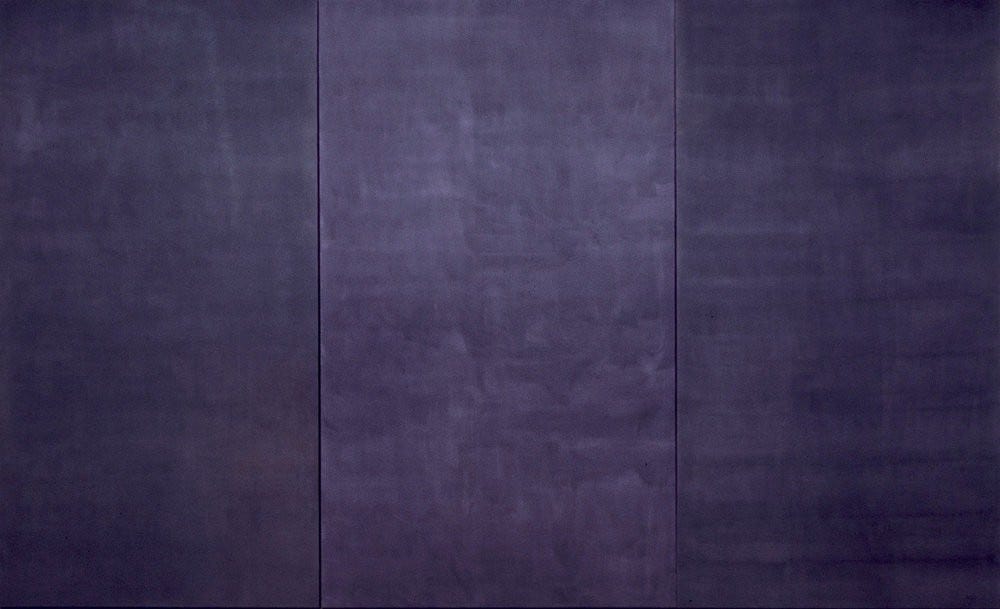

The laws of optics tell us that we distinguish different colors based on their wavelength, which corresponds to a specific frequency. For example, the wavelength of blue is between 465 and 482 nm, while red has a wavelength between 620 and 680 nm. The transition from one shade to another corresponds to a variation in the wavelength of light, which is rapid in the central region of the visible spectrum and slow at its edges. In these regions of the visible spectrum, far from the central region, the hue of the color changes gradually while its brightness or brilliance decreases rapidly, much like the dark and indefinable colors of the 14 paintings of the Rothko Chapel. By introspecting through writing, Rothko discovers a connection between his reflection on death and links it to the experience of color. The chromatic experience remains in the works of the 1950s and early 1960s, but not by chance does it lead to a gradual nullification of depth in the transition from oil to acrylic colors with all the last works and the posthumous canvases exhibited in the Rothko Chapel. These are dark canvases of an indefinable, purplish color, impenetrably opaque to a gaze searching for perceptual footholds, and open in a direction contrary to the wandering of the gaze in the world, created to offer a surface where the eye falls into an inner gaze, where the only discourse is a dialogue of consciousness with itself. The monumentality of what is, in every respect, also an installation, with enormous canvases placed next to each other, indeed creates an immersive experience, the stylistic hallmark of the great American artist. His work is always a painting into which we are "drawn," where the effort is to break the dualism between observer and space, where the work is given to create a whole and nullify any distance between the gaze and the painted surface.

Mark Rothko, The Rothko Chapel, 1965-66. Houston, Texas (Usa).

His refusal to define himself as an abstractionist is driven by his goal of investigating the human soul, rather than creating a pictorial alphabet as an alternative to reality, as was the intention of Kandinsky, for example. On this point, Rothko's approach to painting is clear and radically different: "I am not an abstractionist... I am not interested in the relationship between color and form or anything else... I am only interested in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, and so on. And the fact that many people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate those basic human emotions... The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you are moved only by their color relationships, then you miss the point." (3). His work is one in which the gaze opens and closes within itself; the canvases convey this by pushing the viewer toward a specific path: "Perhaps you have noticed that in my paintings there are two characteristics: either their surfaces are expansive and push outward in all directions, or their surfaces contract and rush inward from all directions. Between these two poles, you can find everything I want to say." (4). The human gaze anxiously seeks meaning and finds rest in naming forms, in giving them identity. In Rothko's color hazes, when he painted in oils, or in the compact walls of his later years with acrylics, there unfolds a parabola that moves from the object, the world, the outward push, back to interiority, to the solitude of the subject. Thus, his discourse is profoundly and radically existentialist.

Mark Rothko, Light red over black, 1957, oil on canvas, 2,3 x 1,5 m. London, Tate Modern.

Is there a link between Rothko's work and music? What sounds are aesthetically closest to this titanic effort to push beyond the visible, beyond perception in a dialogue of self with self? This is helped by the friendship between Mark Rothko and Morton Feldman, which is not only a human relationship but undoubtedly a poetic communion, culminating, not by chance, in the 26 minutes of music dedicated by Feldman to the Rothko Chapel, with which the composer attempts to enter an intimate, suspended, unresolved, and infinite dialogue. Morton Feldman undoubtedly conceived music as a metaphor for painting and maintained that music could learn from painting, “Music is not painting - he writes in “The Anxiety of Art”- but it can learn from this more perceptive temperament that waits and observes the inherent mystery of its materials, as opposed to the composer's vested interest in his craft.”. For Feldman, the encounter with John Cage is essential, from whom he learns the importance of silence as a compositional element, a silence precious also for Rothko. The poetic symbiosis between the two friends, the painter and the composer, is clear, the drive towards an essentiality in music that contemplates on one side suspension and alludes to sound silence and on the other the journey towards the absence of forms first and then even of colors.

Mark Rothko, n°10, 1950

We are faced with one of the last attempts to look at that idea of the sublime and sacred, now inexorably "without God," among the most profound and coherent, both in the field of music and painting, with great influence on generations to come. In the musical field, Feldman's compositions are a cultured prologue, as is also the case for Cage, to all ambient music that delves into both a sonic minimalism and often an introspective dimension that aims to purify the listening experience from perceptual saturation and makes silence one of the main instruments in its becoming. In painting, Rothko opens a steep path "towards the night," interpreting the symbolic dimension of color, a leap beyond the human, not alien to predecessors like Vincent Van Gogh and to artists who came after him, such as Clifford Still, Helen Frankenthaler and Morris Louis.

Bibliography

Mark Rothko “The Artist’s Reality: Philosophies of Art” (2004)

Mark Rothko “Writings on Art” (2006)

James E. B. Breslin “Mark Rothko: A Biography” (1993)

Achim Borchardt-Hume “Rothko: The Late Series” (2008)

Christopher Rothko “Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out” (2015)

Notes

(1) from James E. B. Breslin “Mark Rothko: A Biography” (1993)

(2) from James E. B. Breslin “Mark Rothko: A Biography” (1993)

(3) Conversations with Artists, Selden Rodman, New York Devin-Adair (1957). p. 93.; reprinted as 'Notes from a conversation with Selden Rodman, 1956', in Writings on Art: Mark Rothko (2006) ed. Miguel López-Remiro

(4) from Mark Rothko “Writings on Art” (2006)

Article compiled and edited by Enrico Marani December 3th/2024.

This essay is part of a multimedia project from Spectral Unit (Adi Newton + Enrico Marani).